-

The Taper Tantrums

-

THE MALE ATHLETE TRIAD: PART 2

-

THE MALE ATHLETE TRIAD: Part 1

-

Tips for Picking Running Shoes

-

5 Signs That Your Pain is Nerve-Related Pain

-

Is running bad for your knees?

-

Mostability – The Secret To Better Running

-

Don’t Skip the Warm-Up and Cool-Down

-

THREE SIMPLE SELF-CARE TIPS FOR RUNNERS

-

When Your Race Is Cancelled

-

Pelvic Proprioception: It’s All In The Hips!

-

Are you intrinsically or extrinsically motivated?

-

TEN THINGS TO KNOW BEFORE RUNNING BOLDERBOULDER

-

Tips for Picking Running Shoes

One of the most common questions we get from our runners is in regard to what kind of running shoe they should wear. This happens to also be the most difficult question to answer straightforward! Running shoes are highly subjective and what works for one person may not necessarily work for another. There are so many different brands and models on the market that it can be a bit overwhelming to know where to start. Below we break down a couple of the important concepts when it comes to running shoe style to help you make the best choice.

Do you need stability or neutral shoes?

Stability and motion-control shoes were historically designed to decrease excessive motion at the foot and ankle, such as excessive pronation. Neutral shoes are lighter, a bit nimbler, and allow the foot and ankle to move more naturally. The most important thing to remember when it comes to running shoes is that shoes do not run, PEOPLE do. When a runner is considering what type of shoe he or she needs, controlling motion may not the best approach. Footwear doesn’t necessarily stop or improve any type of foot motion. And often times, people would rather spend money than do the work it takes to improve their bodies and their feet.

We’ve all been told that pronation is bad, but in reality, pronation is a necessary part of the ankle’s shock absorbing system. The issue arises when that motion is uncontrolled due to poor foot and ankle intrinsic strength. Excessive motion at the foot and ankle can lead to a whole host of issues up the chain including plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinopathy, knee pain and hip pain. As a physical therapist, my first line of defense is always to train the body to handle the demands of running. It is a much more sustainable, long term approach to healthy running. A stability shoe can be used in the interim to reduce these forces while a runner is working on improving foot and ankle control, but it should not be a permanent, long term solution.

Lots of cushion vs. minimal cushioning. Which is better and why?

This is a hot topic in the footwear industry right now, with the current trend towards highly cushioned shoes with carbon plates and large stack heights. Did you know that your running mechanics change based on your shoe’s stiffness and the material it is made out of? Shoes with lots of cushioning and a large stack height bring our feet further off from the ground, and as a result, our body loses its sense of where the ground is (or its proprioception). This sensory information from our environment is important because it tells the foot how to properly load the body when it hits the ground. With so much material between the foot and the ground, highly cushioned shoes can create a disconnect between the feet and the brain, causing weak feet and issues up the kinetic chain.

We do know that when you run barefoot, you increase your cadence and you have a shorter step length. In shoes, you put greater negative forces through the knee and the hip because you land stiffer. Imagine running on the beach barefoot as the sand moves underneath your feet. Your body naturally stiffens up as a response to that unstable surface. So, is the answer barefoot running? Absolutely not. Yes, our feet are designed to function without the need for shoes or orthotics, but our bodies are not designed to pound miles and miles of pavement and concrete, like we do in our modern world. Unless you’ve been walking around barefoot your whole life, you probably need some protective, shock-absorbing material between your feet and the road.

Another thing to consider is the heel height of traditional running shoes. A higher heel-to-toe drop (the offset between the height of the back and the height of the front of the shoe) shifts the low back into extension and puts the load through the knees. This moves the body towards a more quad-dominant position and makes it harder to engage your glutes (the backside of the hip, a runner’s powerhouse) when running.

I always direct my runners towards a shoe in the middle of the spectrum in terms of stack height, cushioning and heel-to-toe drop, unless they already run in minimalist shoes with no problems. If you’re an urban runner and log most of your miles on hard surfaces like pavement and concrete, it might be worthwhile to have a pair of cushioned shoes in your closet to use occasionally for minimizing the harsh impact of those surfaces. I also recommend my runners rotate through a couple different types of shoes, so they aren’t running in the same shoe every day.

Racing flats vs. everyday trainers.

Racing flats differ from everyday trainers in that they are designed to be lighter, faster and more minimal than the traditional training shoe. A racing flat has enough cushioning for a distance race, but is essentially a stripped down, faster version of a trainer. And racing flats are proven to be faster than trainers. Racing flats are a great compliment to your training for faster efforts like tempos and threshold intervals, especially if you plan to race in your racing flats. They give you a better feel for the ground and do a better job and teaching your foot and ankle how to act as a shock absorber and propulsive force. However, I wouldn’t recommend using them for a majority of your runs because they are more minimal, especially if you primarily run on harder surfaces. If you already have a dependable pair of trainers and are looking for a secondary shoe, a racing flat or slightly lighter, more minimal trainer can be a great compliment to your training.

Does brand really matter?

Prominent biomechanist Benno Nigg published a heavily referenced study about running shoes that found that comfort, above all else, was the best determinant of a shoe’s utility. How well the shoe fits your unique foot and how it feels is more important than any flashy technological advancement. That being said, try on a bunch of different shoes to see what feels and works best for you.

As a PT, I rarely recommend a particular brand of shoe to my runners. Instead, I give them guidelines for the technical aspects they should be looking for in a shoe (level of cushioning, heel-to-toe drop, stack height, midsole stiffness). Be well informed before you walk into a running store and don’t buy into the hottest, flashiest shoe craze on the market.

Is it better to go to a store to try on shoes or can I order a bunch online?

Ideally it is best for you to be able to try different pairs of shoes on if you don’t have a good idea of where to start. Some online retailers will let you return shoes easily if they do not work for you. Some running stores also have lenient return policies that will let you try out the shoe for a bit before deciding to return it or not. Regardless of which outlet you choose, be sure to read all the fine print so you aren’t stuck with a shoe that ends up not working for you!

Other important things to note

Most running injuries are repetitive stress injuries that occur from the same stimulus or load applied to a tissue over and over again. Studies show that we can reduce injury risk by switching up your running shoes regularly. You can give your body a different stimulus by wearing a different shoe now and then which will put the foot in a different position and load different tissues.

When considering switching from one type of shoe to another, depending on how far they are from each other on the spectrum of minimalist-maximalist shoes, allow your body a long period to transition. If you’ve been running in highly cushioned maximalist shoes, do not buy a new pair of neural shoe and start doing all your runs in them. There should be a transition period (anywhere from a couple weeks to a couple months) where you gradually introduce the new shoe to your body and your feet. This method of graded exposure is a much more effective way to get into a different type of shoe without increasing your risk for injury.

-

THE MALE ATHLETE TRIAD: Part 1

What is the Male Athlete Triad?

Over the past 30 years, research has developed our understanding of the Female Athlete Triad. More recently, research has shed more light on The Male Athlete Triad, a similar condition affecting men. While awareness about the Female Athlete Triad has grown in the endurance community, many are unfamiliar with The Male Athlete Triad.

Each of these conditions fall under the umbrella of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport, or RED-S, a broader condition affecting both women and men. These are problems related to prolonged training in an energy deficient state, aka a state of low energy availability in the body.

Imagine the energy your body uses as money. This money is energy availability. For the sake of the metaphor, let’s call this, “energy dollars.” Eat breakfast? That’s a direct deposit of energy dollars into your body’s energy availability checking account. Going for a run? Time to make a withdrawal.

This is how our body works (albeit very oversimplified). You wake up and eat a bagel. Boom, 5 energy dollar deposit – you have energy available and are ready to run. Your run costs you 3 energy dollars. Your body makes physiological adaptations and you become a little faster.

Let’s say after you eat your bagel ($5 deposit), you go for a long run that costs 6 energy dollars and overdraft your checking account. That’s okay, your body can take out an energy dollar from your savings account – energy stored elsewhere in the body. Afterwords, you refuel, and your body builds back stronger.

But let’s say you don’t refill your accounts. And you do this day after day. Your checking and savings accounts are running dry, you’ve spent all your energy dollars and you go into energy debt. You are training in a state of low energy availability. Let’s step away from this kooky metaphor for a minute to look at a study:

In this study, runners reduced energy intake 50% of daily needs and ran 60 minutes on a treadmill every day for 3 days. This caused a 15% decrease in bone formation. In just 3 days! When we continue training in an energy deficient state, with an empty energy availability bank account, our body shuts down other critical processes in our body because there just aren't the funds for it. We have no resources to direct towards building back bone or recovery because in our low energy availability state, everything we have is going towards training. The longer we train with improper fueling, the more these effects are compounded. This is the root of Relative Energy Deficiency Syndrome, or RED-S, and it can manifest in dysfunction of metabolic rate, menstrual function, bone health, immunity, protein synthesis, cardiovascular health, and other bodily systems.

The Male and Female Athlete Triad’s each involve 3 interrelated conditions secondary to training in an energy deficient state. The Female Athlete Triad was coined prior to RED-S over 30 years ago. It consists of low energy availability, altered bone mineral density, and menstrual dysfunction. Increased research in recent years on the Male Athlete Triad has furthered our understanding of the condition, and like The Female Athlete Triad it is important to know how to recognize and address it.

What is the Male Athlete Triad?

3 interconnected conditions make up the triad:

1) Low energy availability (EA) – put simply, more energy is going out than coming in. To return to our metaphor, the body is operating without energy dollars in the bank and is paying for activity with credit – other bodily functions are suppressed as the athlete continues to train in an energy deficient state. Low EA can be present with or without disordered eating.

2) Impaired Bone Health – as illustrated by the study mentioned above, operating in an energy deficit has significant impact on the body’s bone health. Low bone mineral density is present in a bigger proportion of lean-sport athletes like runners, swimmers, jockeys, and cyclists.

3) Suppression of hormone function – Specifically, the hypothalamic-pituitary gonadal (HPG) function, resulting in decreased testosterone concentrations and decreased sex drive.

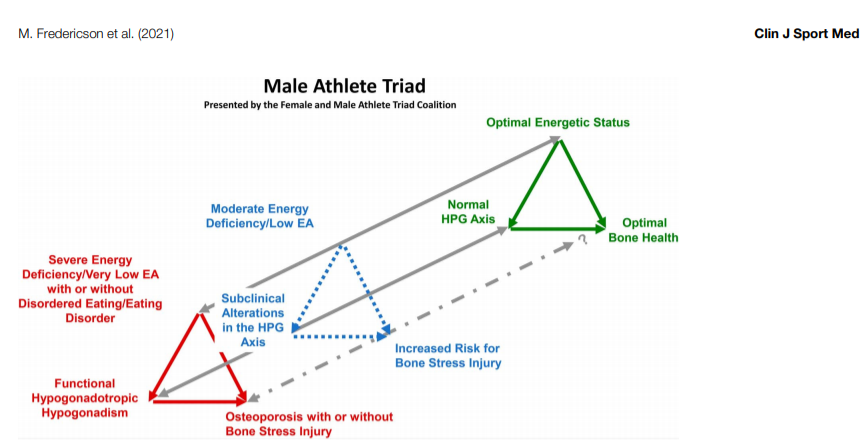

It is important to note that the male athlete triad is a continuum. There is no exact threshold value of energy availability that once crossed leads to metabolic changes and dysfunction. Instead, we see a spectrum: on one end we see optimal energy availability, bone health, and hormonal function, and on the other severely low energy availability, osteoporosis/possibly bone stress injuries, and Hypogonadaropic Hypogonadism (negative hormonal changes). These changes happen over time when training with low EA. When caloric intake is not enough to fulfil the cost of training load, athletes begin to go into “energy debt.” Initially, athletes may be able to perform well in a state of low EA, but it is not sustainable as they will continue to move towards the unhealthy end of the spectrum.

Athletes with or without disordered eating can experience the Male Athlete Triad. 8% of male athletes develop eating disorders, and this number is higher among “leanness sports” like running, swimming, and cycling. Unintentional undereating can also lead to low energy availability. However, it is not always a simple equation of caloric intake equaling energy expended during training to avoid going into energy debt. Oftentimes athletes fail to consider the impact of being a human being and dealing with the daily stressors of life! Life load and the stresses that come along with it can have an impact on our energy availability. Jobs, school, relationships, sleep, stress, quality of food, and difficult life events are all important parts of the equation that demand energy, and are important for any coach, athlete and clinician to remember.

Male athletes that continue to train with energy debt, aka in an energy deficient state, begin to demonstrate objective changes that indicate long term energy deficiency. This is as a result of not having energy remaining after the cost of exercise for the body’s basic processes, and includes:

- Changes in metabolic hormones (i.e., decreased testosterone)

- Lower resting metabolic rate (RMR) - the body suppresses the energy directed towards basic bodily processes to conserve energy

- Changes in body weight and composition

Subjective indicators and symptoms are also important to monitor and can warrant further screening. Examples include:

- Persistent fatigue and lethargy – this one can be tricky. For many endurance athletes, fatigue is a part of training. We all know the feeling of being in the middle of a training block and feeling tired just walking up a flight of stairs. Fatigue is a part of endurance sports. However, concerning signs may include feeling fatigued after appropriate rest days, when expected to be relatively fresh for intense training sessions, or fatigue that carries through tapering.

- Decreased libido and the absence of morning erections

- Decreased beard growth – needing to shave less often

- Negative performance changes in their sport

- Mood changes that are unaccounted for

- Getting sick more often than normal

- Recurring injuries

These can occur over weeks to months of training in a depleted state. It is important to evaluate these changes and symptoms in conjunction with one another. Low BMI for example is a common characteristic among runners but alone does not mean an athlete has low energy availability. One indicator is not enough to diagnose RED-S or the Male Athlete Triad; it is a multifactorial condition and should be evaluated and treated as such. Keep an eye out for a part two on this topic with information on how to screen for, evaluate, and manage athletes experiencing The Male Athlete Triad.

References:

Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, et al. The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female Athlete Triad—Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). British Journal of Sports Medicine 2014;48:491-497.

Nattiv A, De Souza MJ, Koltun KJ, Misra M, Kussman A, Williams NI, Barrack MT, Kraus E, Joy E, Fredericson M. The Male Athlete Triad-A Consensus Statement From the Female and Male Athlete Triad Coalition Part 1: Definition and Scientific Basis. Clin J Sport Med. 2021 Jul 1;31(4):335-348. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000946. PMID: 34091537.

Fredericson M, Kussman A, Misra M, Barrack MT, De Souza MJ, Kraus E, Koltun KJ, Williams NI, Joy E, Nattiv A. The Male Athlete Triad-A Consensus Statement From the Female and Male Athlete Triad Coalition Part II: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Return-To-Play. Clin J Sport Med. 2021 Jul 1;31(4):349-366. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000948. PMID: 34091538.

Raj MA, Creech JA, Rogol AD. Female Athlete Triad. 2021 Aug 14. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan–. PMID: 28613538.

-

THE MALE ATHLETE TRIAD: PART 2

Diagnosis and Management of The Male Athlete Triad

To recap part 1, we know that The Male Athlete Triad is comprised of three interrelated conditions:

1) Low energy availability (EA): Energy intake < Energy expended. Important bodily functions are suppressed as the athlete continues to train in an energy deficient state. Low EA can be present with or without disordered eating.

2) Impaired Bone Health: Low bone mineral density, often manifesting in bone stress injuries in athletes.

3) Suppression of hormone function: Specifically, the hypothalamic-pituitary gonadal (HPG) function, resulting in decreased testosterone concentrations and decreased sex drive.

But how do we prevent and identify The Male Athlete Triad in athletes?

Increased awareness of signs and symptoms among medical professionals, coaches, parents, athletes, and sports organizations is an important step, but early screening and monitoring for RED-S and the Male Athlete Triad must become common practice for at-risk groups.

At-risk groups for developing 1+ components of the triad include “adolescent and young adult male athletes in sports that emphasize a lean physique (lean-sport athletes), especially endurance and weight-class athletes.” Screening of athletes in these sports (distance running, swimming, cycling, wrestling, etc.) should be a part of pre-participation physical exams beginning in middle school. While especially important in middle school – college-aged athletes due to peak bone development happening during this time, it is also important to continue to screen post-collegiate athletes in lean-sports. Formal screening should also happen when an athlete presents with common symptoms of the Triad :

- Persistent fatigue and lethargy – this one can be tricky. For many endurance athletes, fatigue is a part of training. We all know the feeling of being in the middle of a training block and feeling tired just walking up a flight of stairs. Fatigue is a part of endurance sports. However, concerning signs may include feeling fatigued after appropriate rest days, when expected to be relatively fresh for intense training sessions, or fatigue that carries through tapering.

- Decreased libido and the absence of morning erections

- Decreased beard growth – needing to shave less often

- Negative performance changes in their sport

- Mood changes that are unaccounted for

- Getting sick more often than normal

- Recurring injuries

Many endurance athletes have experienced or know of someone who has sustained a bone stress injury (BSI). It’s crucial to complete screening for other components of the triad when BSIs occur to prevent more serious outcomes, like long-term hormonal function and bone health, to name a couple.

What is involved with screening?

Unlike the Female Athlete Triad, at this time there are limited screening tools that are practical and specific to The Male Athlete Triad.

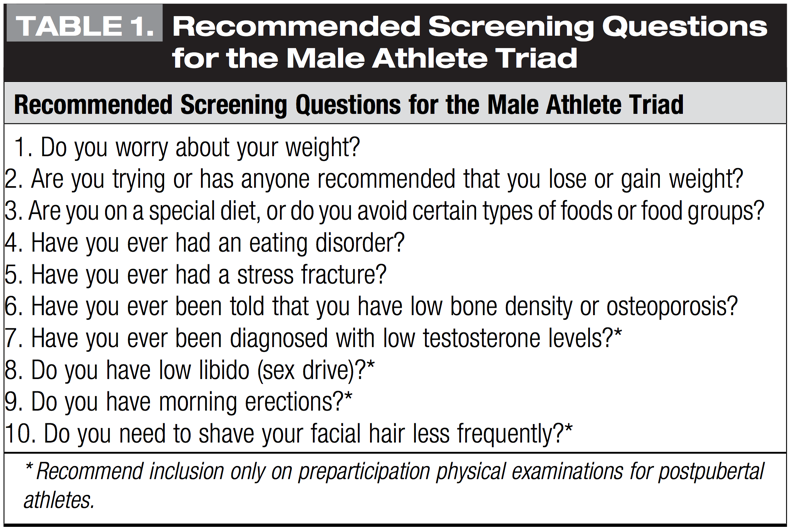

Fredericson et al. (2021) recommends the questions listed in the table below as a screening tool. It’s important to keep in mind that male athletes do not need to be actively restricting intake or losing weight to develop the Triad. While disordered eating or concerns about weight are risk factors related to the Triad, they are not always present in cases of the Male Athlete Triad.

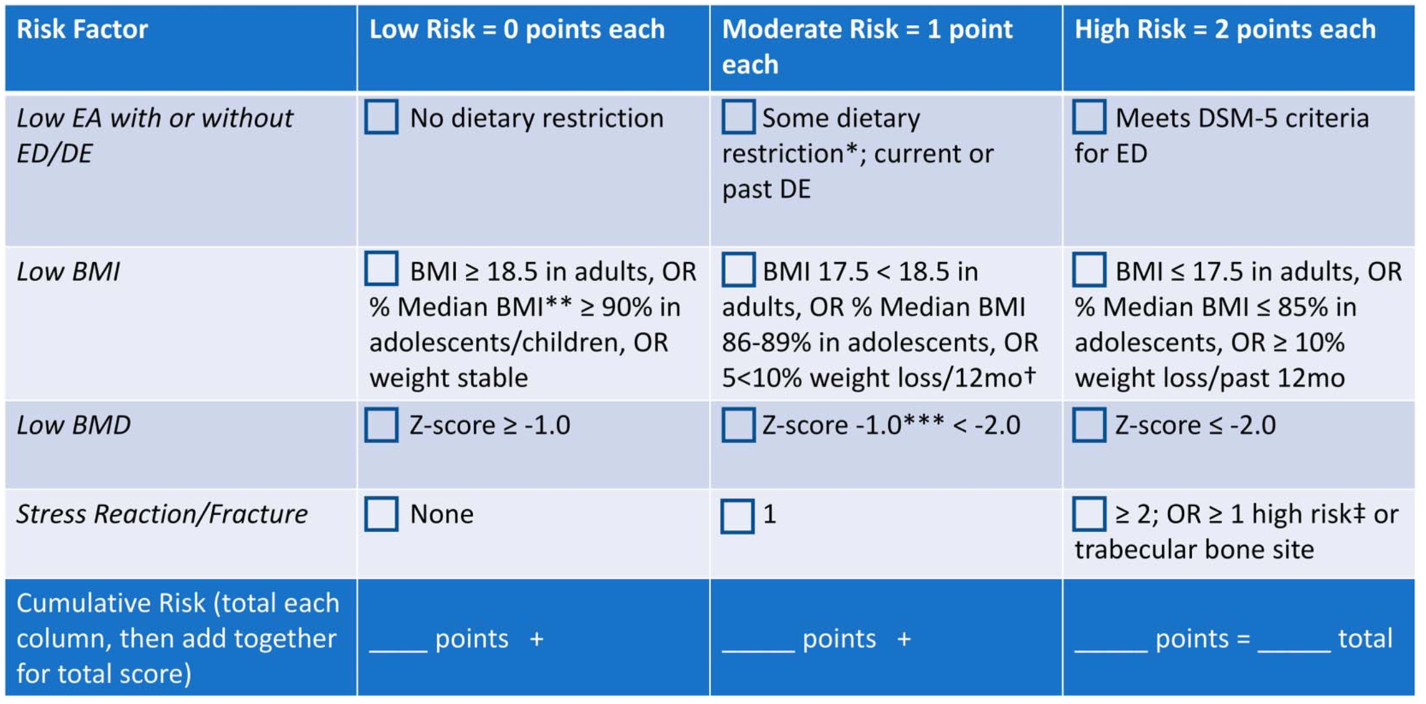

Kraus et al (2019) developed the risk assessment tool below which can be used to identify risk for The Male Athlete Triad and guide return to sport decisions, particularly when returning from bone stress injury or series of bone stress injuries.

Management of the Male Athlete Triad

If you take one thing away from this, take this: it takes a team approach to successfully diagnose and manage the Male Athlete Triad. This multidisciplinary team should include:

-

- Team Physician or sports specific physician

- Sports Dietician

- Mental Health Professional if disordered eating or eating disorder is present.

- Physical Therapist or Athletic Trainer competent in managing energy deficiency in sport.

- The Athlete! In youth athletes, parents should be a part of this team as well

- Endocrinologist when hormonal involvement (Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism) present

The team approach is crucial to identifying and managing the components of the Male Athlete Triad. It is crucial to explore both signs and symptoms, and athlete behaviors in detail. Dietary behaviors, weight changes, weight goals, behaviors to control weight are all intertwined with endurance sport. Weight does impact performance. Endurance athletes tend to be very lean, and low BMI is often the nature of the sport. But absolute BMI is not the best method to reflect nutritional status in youth with disordered eating. As of now, there is no exact way to measure EA. Identifying behaviors that contribute to undereating (intentionally or unintentionally), along with medical history and other factors, is the best approach for identifying low EA. Working with a multidisciplinary team can help athletes better understand how to optimize performance while maintaining appropriate energy availability is important to avoid crossing into energy-deficient territory and increasing risk of the Male Athlete Triad.

Treatment

To return to our metaphor from part one, the priority of treatment should be restoring energy dollars in your checking account, and keeping your account in the green while training. In other words, returning to a state of adequate energy availability and maintaining it with training is critical.

Optimizing fueling by ensuring high nutrient snacks and meals around training sessions so that the athlete can perform well and recover well will not only prevent health consequences but will lead to better, more consistent development and performance.

Dieticians can help to ensure adequate macro and micronutrients – supplements may be helpful but the goal is getting most of these nutrients from the diet when possible. Participation in weight-bearing sports or plyometric cross-training with multidirectional movements can be helpful for bone health. Multiple studies show time and time again that strength training has protective effects against bone stress injury.

Again, the Male Athlete Triad is multifactorial with several physical, social, and mental factors playing a role. This is where the team approach comes in – addressing all of the contributing factors and underlying causes is important and requires this multifaceted approach.

There is no gold standard for clearing an athlete to return to sport. Many times the return comes after repetitive injury or bone stress injury. The Male Athlete Triad Cumulative Risk Assessment tool mentioned earlier has guidelines for returning to sport based on risk factors in the individual athlete. Again, this tool should be used at regular pre-season exams, or when signs/symptoms of the triad arise.

Recommendations for the endurance community

Sports teams should incorporate education on nutrition and fueling to perform. Keeping the energy “bank account” full going into workouts and post-workouts to ensure appropriate energy availability is important. Coaches, teams, parents, and healthcare professionals should be mindful of the language they use, with a focus on optimizing energy availability, rather than increasing body weight. Healthcare providers must be comfortable with asking uncomfortable questions related to libido and sexual function – questionnaires can be a helpful tool for navigating this, but it must be a part of pre-participation exams in at-risk athletes and incorporated when concern for the Male Athlete Triad is present.

Discussion about body image and views can be important in uncovering athlete beliefs and potential risk factors. Establishing a positive training environment, free of critical comments specific to body shape and weight, and rather focused on strong and healthy athletes is important. Creating realistic and healthy goals related to weight and body comp with the help of a dietician can be beneficial. And creating awareness that good performance does not always indicate that an athlete is healthy – focus on maintaining a state of energy availability that will lead to sustainable healthy training and therefore more consistent positive results.

Reversibility of the Male Athlete Triad is possible with proper management, but the timeline for recovery is based on the severity and how long an athlete has been training in an energy-deficient state.

For more information on RED-S and The Male Athlete Triad, check out the articles referenced below:

References

Kraus E, Tenforde AS, Nattiv A, et al. Bone stress injuries in male distance runners: higher modified female athlete triad cumulative risk assessment scores predict increased rates of injury. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:237–242.

Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, et al. The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female Athlete Triad—Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). British Journal of Sports Medicine 2014;48:491-497.

Nattiv A, De Souza MJ, Koltun KJ, Misra M, Kussman A, Williams NI, Barrack MT, Kraus E, Joy E, Fredericson M. The Male Athlete Triad-A Consensus Statement From the Female and Male Athlete Triad Coalition Part 1: Definition and Scientific Basis. Clin J Sport Med. 2021 Jul 1;31(4):335-348. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000946. PMID: 34091537.

Fredericson M, Kussman A, Misra M, Barrack MT, De Souza MJ, Kraus E, Koltun KJ, Williams NI, Joy E, Nattiv A. The Male Athlete Triad-A Consensus Statement From the Female and Male Athlete Triad Coalition Part II: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Return-To-Play. Clin J Sport Med. 2021 Jul 1;31(4):349-366. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000948. PMID: 34091538.

Raj MA, Creech JA, Rogol AD. Female Athlete Triad. 2021 Aug 14. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan–. PMID: 28613538.

-

The Taper Tantrums

Have you ever noticed that your body may feel different when you start to taper for a big race? Legs may feel heavy, energy levels might be low, and little niggles or aches and pains can pop up almost seemingly out of nowhere. To have crappy workouts leading into a big race is actually normal when you taper. Here’s why:

First, since you’re so focused on how your body is feeling leading up to race day, you can be more hyperaware of every little ache and pain. The brain is a powerful thing and can often magnify these perceptions.

Your body functions via two primary nervous systems – the sympathetic (fight or flight) and parasympathetic (rest and digest) nervous systems. Our sympathetic nervous system is dominant during periods of heavy training (similar to the stress of cramming for a big exam), and then we crash during taper when volume and intensity decreases.

During peak training, the body is on overdrive, regularly secreting adrenaline and producing endorphins. Now that you’ve backed off training, your body does not produce as much of these hormones, leaving you feeling tired and lethargic. This is normal!!

Microdamage sustained to soft tissues during heavy training is also now given time to repair. This can sometimes cause soreness or cramping/twitching in your muscles as the body adapts. Again, completely normal so no need to panic!

Hard and intense training can temporarily suppress your immune system. As you taper, the immune system kicks into overdrive and your chances of catching a cold are higher. Do all the little things to stay healthy (sleep, hydration, eating well, washing your hands, etc.).

All of these things are normal and a sign that the taper is working! (If you don’t have any of these issues, don’t worry, it’s still working). Trust in the process and have a great race!

-

5 Signs That Your Pain is Nerve-Related Pain

One of the most challenging aspects of my job as a sports physical therapist is determining what tissue in the body is the source of a patient’s pain. There are a variety of types of tissue sources of pain and sometimes an injury can cause multiple. Because all muscles, tendons and soft tissues in our body are innervated by nerves, a foot problem could very well be manifesting from a nerve-related problem else where in the body. Nerves run from head to toe so any kink or sensitivity long that nerve route can potentially cause pain (think kinks in a long hose).

Nerve-related pain is a lot more common than most practitioners realize, especially in the athletic population. Probably 20% of injuries I treat in runners, cyclists and triathletes are actually nerve related pains that present as a muscle, tendon or other soft tissue injury.

What is nerve pain?

Nerve (or neurogenic) pain can occur any time a nerve is sensitized. This sensitization can happen at any point along a nerve’s trajectory - from the point where it exits the spinal cord in the spine, and along the the nerve’s route to any of our limbs. Once a nerve is irritated, it can be very sensitive to stretch, compression and even chemical changes (hormones, inflammation from another local tissue) in the body.

Nerve pain can be peripheral (an irritation to the nerve along its route as it goes throughout the body’s limbs), or central (originating from the spine). Central pain can often refer peripherally to various parts of the arms or legs and mimic other orthopedic or musculoskeletal injuries.

So how do you know if your pain is nerve-related pain? Nerve pain can be tricky to diagnose but there are few patterns that are worth pointing out:

1. Your Pain Doesn’t Respond to Traditional Treatment - if a patient comes into my clinic with an injury that failed to resolve with other PT, I always look at the spine or for neurogenic symptoms. If you’re treating a distal injury and it is not responding, always look up the chain! I had a patient come in with lower leg pain that wouldn’t resolve with previous massage, dry needling, or soft tissue work. I looked further up into her hip and low back and found that her pain was actually referral pain along the sciatic and common fibular nerves.

Traditional treatments for musculoskeletal injuries - soft tissue work, stretching, strengthening, dry needling - usually fail to resolve nerve pain if you are being treated peripherally. There is no injured tissue there. Aggressive foam rolling and stretching can also make an irritated nerve more unhappy.

2. Your Pain is Dull, Diffuse, Hard to Pinpoint, or Moves Around - a soft tissue injury like a muscle strain or tendinopathy is usually pretty easy to pin down. Location and pattern of pain are fairly consistent and localized. Nerve pain can be elusive and difficult to pinpoint where it hurts. And palpating the tissue often does not result in that familiar pain (or any pain at all). If you feel pain in a certain area but touching that tissue does not result in that same pain, it’s likely what you are feeling is referred pain - pain referred to that area from a location further away. Nerve pain can be dull, achy, diffuse, sharp, shooting or accompanied by pins and needles.

3. Your Pain is Variable and Doesn’t Relate to Activity Level - when patients come in with nerve-related pain, it is difficult for them to find a pattern of pain. It’s not predictable or consistent with their activity level. Sometimes they have pain from the first step of running, sometimes they don’t. Sometimes it gets better throughout a run, sometimes worse. They might also have pain just sitting on the couch. Sometimes the pain moves from one part of the body to another, anywhere along that nerve’s distribution.

4. You Have Pain at Rest - this is an important one. Random jolts of pain just sitting on the couch or lying down in bed can signal nerve or referred pain. If the nerve pain is a result of nerve entrapment or compression elsewhere, rest will not make it better. Unless you have an acute orthopedic injury, having symptoms at rest can be a red flag for nerve pain.

5. You Get No Answers From Diagnostic Imaging - nerve pain or an irritated nerve does not present itself on MRI or Xray. When a patient doesn’t respond to traditional PT, imaging is often the next route. So it can be disappointing when an MRI or Xray shows no pathology at all. An even more serious consequence is when the imaging shows pathology that isn’t necessarily related to that patient’s pain. I see this WAY too often and it can be even more psychologically damaging.

- Example #1: Patient with low back pain gets MRI and finds he has a herniated disc in his lumbar spine. He comes to me and I find out that his pain is actually referred pain from his glutes - it clears up after a few sessions.

- Example #2: Patient with anterior hip pain gets MRI to find she has a labral tear in her hip - she’s told she needs surgery to repair it. She comes to see me and I find out that she has a femoral nerve entrapment in the front of her hip.

Common areas of pain in endurance athletes and possible nerve culprits:

Injury/Area Possible Nerve Involvement Posterior pelvis, hip (butt) Cluneal, sciatic, obturator nerves Anterior and lateral hip and thigh Cluneal, sciatic, lateral femoral cutaneous nerves Medial thigh and knee Femoral, obturator nerve Lateral shin Superficial fibular nerve Medial shin Tibial nerve Lateral ankle Sural nerve Medial ankle Tibial nerve Bottom of the foot Medial and lateral plantar nerves Top of the foot and toes Superficial, deep fibular nerves All of these above areas of the body are also innervated by specific levels of the spine (L2, L3, L4, etc.). Pain in these regions could also be originating from your back or spine, what we call radicular pain. It's also important to note that every muscle has its own referral pattern. While not necessarily nerve-related, pain can present distally and still be coming from a muscle up the chain. Sound complicated? Not necessarily if you can recognize these patterns!

So how do you treat nerve pain?

Remember that water hose analogy above? When considering where to best target your treatment efforts, you need to consider the length of the nerve at play and where is runs. For healthy nerve conduction, the entire length should be uninterrupted and uninhibited. Gentle manual work can help to address any “sticky” areas along the nerve course, including where it originates in the spine.

Sensitized nerves also respond best to gentle mobility to promote blood flow to the tissues. Functional dry needling with electrical stimulation can also be a fantastic tool for nerve and referred pain, as it can really target the release of tissues impeding the nerves, as well as provide signal input and stimulation to help the nerves properly fire

So whether you’re a runner, a cyclist or a triathlete, be cognizant of the importance of the nervous system and the role it can play in your pain or injury. If you’re struggling with pain, make an appointment to see a physical therapist today!

-

Is running bad for your knees?

You’ve probably heard people claim that running is bad for your knees, that all that impact can lead to early development of osteoarthritis. Is there any basis for this traditional claim? Well, truth be told, there isn’t much. In fact, the prevalence of hip and knee osteoarthritis in recreational runners is 300% lower than in sedentary individuals.

A quick anatomy lesson:

Osteoarthritis (OA) refers to aging of a joint. It occurs when the protective cartilage in the joint wears down over time. Cartilage is soft tissue that helps to reduce friction between two bones, allowing you to move more easily. OA a COMMON side effect of aging (like graying hair or wrinkles). Symptoms include joint pain, stiffness (especially in the morning), and swelling. There are different grades of OA - Stage 1 refers to minor wear and tear, while Stage 4 is the most severe on imaging, often resulting in a joint replacement surgery.

Research has shown that 40-50% of people 40 years of age and older have OA changes on X-ray but have NO pain. There’s also a lot of research out there comparing characteristics of these asymptomatic individuals to those with pain. Why do some individuals with OA have pain, and some do not?

How does running improve knee health?

In one research study, subjects started a 10-week running program. They had an MRI before and after the program. Researchers noticed that for those who started running, there were actual changes in their cartilage after 10 weeks. They found higher concentrations of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in the cartilage, which are important molecules for physiological functions. By attracting water in the cartilage, GAGs can make the cartilage more tolerant to loading. So over the course of 10 weeks, these runners improved the loading capacity of their cartilage, just by stimulating it with impact.

A 2019 study by Horga et.al found that training for and running a marathon can also improve different features in the knee. Results showed that there was reversibility in the damaged subchondral bone of the tibia and femur in novice runners after training for and running a marathon.

What does all this mean?

Well primarily, running does not wear out the cartilage in your knees! But there’s a slight caveat to that statement. In a study looking at changes on x-ray for hip and knee OA, researchers found that competitive (international or world class) runners had a 13.3% prevalence of OA, which was more than non-runners and sedentary people (10.2% prevalence). Recreational runners had only a 3.5% prevalence. So it appears that too much of a good thing can be, well… not as good. That’s not too surprising. But for recreational runners (even running up to 40-50 miles a week), you can reverse aging effects of the knee joint.

How to safely run with OA

We know that running is safe for those who have grade 1 or 2 knee OA. Based on current literature, running does not progress knee OA in people who run. If running isn’t painful, you can continue to run, even if you have OA findings on imaging. For those with mild OA, it is normal to feel something mild in the joint when you run, as long as symptoms return to baseline within the hour after you stop. In addition, there should not be any increase in stiffness or swelling the day after.

If you are symptomatic, it’s important to consider load when planning your runs. Instead of long duration and less frequency, consider shorter but more frequent runs to reduce peak load and magnitude. It is better to distribute the load across more sessions so there is less load at a given time for the joint.

For example, instead of 3 x 60-minute runs a week, try running 5-6x a week for 20-30 minutes each run.

Running twice in the same day can also be helpful. You still get the adaptations but you’re staying under the body’s load threshold.

Footwear considerations

The new trend in footwear these days is cushion cushion cushion! Shoes companies claim that these maximally cushioned shoes take lots of force and load off the body. Most of you may also believe that by putting more cushioning under the foot, you decrease the impact forces and load through your joints. HOWEVER, it’s actually the opposite. Impact and loading (particularly at the knees) INCREASES in highly cushioned shoes.

Consider how your body reacts when running barefoot on concrete vs running on sand or a trampoline (go ahead, try it and compare). We must stiffen up our bodies in response to more unstable surfaces, as opposed to landing softer on harder surfaces (try to land with a stiff leg on concrete… ouch!). Shoes change the way people run. The more cushioning, the higher the stack height, and the farther your foot is off the ground. If you cannot feel the ground under your foot because you have so much cushioning, you will inevitably land with a stiffer, harder leg. You won’t necessarily feel it with each step, but over time the load applied through the knee joint will be much greater than it would be with a neutral shoe.

In Conclusion

You can’t afford to NOT run for the health of your joints across your lifespan. Healthy loading stimulates positive adaptations, not only for your musculoskeletal system, but for every system in your body. If you’re running with OA, consider spreading out your runs so each one is shorter, but you’re running more frequently. In terms of what type of footwear is best, it’s also important to consider shoe’s level of cushioning. A highly cushioned shoe may not be the best choice to reduce excessive impact forces through a knee that has limited loading capabilities.

References:

Alentorn-Geli E, Samuelsson K, Musahl V, et al. The association of recreational and competitive running with hip and knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy.2017;47(6):c373-390.Davis IS, Rice HM, Wearing SC. Why forefoot striking in minimal shoes might positively change the course of running injuries. J Sport Health Sci. 2017;6(2):154-161.

Davis, IS. Shifting paradigms in the approach to footstrikes, footwear and treatment of the foot. J Foot Ankle Res. 2011;4. 1-1. 10.1186/1757-1146-4-S1-A3.

Horga LM, Henckel J, Fotiadou A, et al. Can marathon running improve knee damage of middle-aged adults? A prospective cohort study. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2019;5(1):e000586.

Laskowski ER, Newcomer-Aney K, Smith J. Refining rehabilitation with proprioception training: expediting return to play. The Physician and Sports Medicine. 1997;25(10).

Riva D, Bianchi R, Rocca F, Mamo C. Proprioceptive Training and Injury Prevention in a Professional Men's Basketball Team: A Six-Year Prospective Study. J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(2):461-475.

-

Mostability – The Secret To Better Running

There's a lot of talk these days on the topic of 'mobility' in terms of sports performance and injury prevention. Runners are always looking for ways to improve performance while simultaneously avoiding those annoying overuse injuries. While mobility is one of the most important aspects of sport, it ties heavily into stability. You can't have one without the other. Mobility without stability and vice versa can lead to subpar performances, poor movement patterns and injuries. This leads us to the topic of MOSTABILITY = mobility + stability. Mostability is a term coined by Dr. Gary Gray of the Gray Institute to blend both elements to complete a desired task (i.e. running).

MOBILITY = the ability of your joints to move through a given range of motion

STABILITY = the ability of the body to maintain postural equilibrium and support joints during movement

There’s a reason why we feel tightness in muscles or joints. Our perception of this tightness is not necessarily related to an overworked muscle and does not always mean that we should stretch it. But rather, the body’s nervous system is telling you that there’s instability in that region. Instability signals the brain and nervous system to put the brakes on because it feels threatened. It does this by borrowing stability from somewhere else to provide a sense of security. This is called compensation. This compensation is the tightness that we feel.

As the Gray Institute says:

“Just as important, but not as obvious is the 'mostability' of the pelvis when our foot hits the ground in running. At ground contact, the posterior-lateral muscles of the hip have a large role in decelerating the motions of the hip, knee, and foot created by gravity and ground reaction force. These muscles need the pelvis to be a stable base from which to generate force, but the pelvis is moving. So again, both stability and mobility are necessary. During running, the one foot will be in the air when a stable yet mobile pelvis is required. How does the pelvis remain stable while it is moving without the connection to the ground? The mass and momentum of the swinging leg, trunk, and arms all contribute to the ability of the pelvis to have 'mostability'.”

So how can you incorporate mostability into your routine? Below is an example of an exercise that we use at BUILD to help runners achieve dynamic single leg strength, stability and mobility at the pelvis.

REVERSE LUNGE with STEPOVER

The hip joint is a dynamic joint that can move in all 3 planes of motion. This exercise is great for runners in that it three dimensionally combines single leg balance, stability and mobility all in one. The focus should be on gaining mobility through the hip joint of the standing leg, so be sure to really open up your trunk, as shown in the video below. Performing the exercise barefoot may be more difficult but will yield better proprioception integration of the foot and ankle. Try it with body weights or with a dumbbell out in front for added trunk and shoulder recruitment.

-

Are you intrinsically or extrinsically motivated?

This is probably one of the most valuable pieces I’ve written this year. Cancelled races, lack of motivation, decreased compliance to training plans, etc. Those who take personal enjoyment in their activity of choice have been able to persevere throughout this pandemic, while those motivated solely by the finish line, finisher’s medal or the bragging rights have found themselves at a loss for what to do.

Intrinsic motivation involves doing something because it is personally rewarding to you and brings you satisfaction. You genuinely enjoy and seek the growth of knowledge and personal development it brings you.

Extrinsic motivation occurs when your behavior is dictated by an external factor pushing you towards a finish line (pun intended). You require a reward OUTSIDE of yourself to be motivated (training for an upcoming race, making the podium, or qualifying for a world championship, etc.).

But this global pandemic has shaken our system, our normal way of functioning. Those of us who are extrinsically motivated have felt lost and without a sense of purpose. Some have been able to keep their motivation up with small goals, chasing KOMs, doing personal time trials, but not everyone.

So which form of motivation is the most sustainable? In my experience, the constant high of chasing external finish lines, podiums and KOMs diminishes over time, can lead to burnout, and can actually decrease someone’s intrinsic motivation. Rewards have their uses, but intrinsic motivators hold the real power, satisfaction and longevity.

If you’re a finish-line chaser who has been struggling with sports being cancelled, maybe take this pandemic to search for some internal factors that bring you enjoyment, motivation and personal fulfillment to your life. Find that internal drive, that biological motivation, that purpose. Learn how to reach your true potential without relying on external sources.

How? This leads us to the three elements of intrinsic motivation and how to incorporate them into your daily lives:

Autonomy | If people are in complete control of their experience and outcome, they are more likely to fuel their own motivation. Autonomy also allows for greater creativity and independence from outside sources. To be fully intrinsically motivated, you must be in control of what you do and when you do it. I’ve actually advised some of my athletes who were struggling with motivation to take some time off, not from exercising but from structure, to have them dictate their own schedules to do what they want, when they want.

Mastery | The desire to improve, to attain the utmost knowledge for a subject, activity or task. Mastery will enable someone to seek their true potential. I have an athlete who is motivated to be a stronger, faster runner. Any finish line or medal is less important than the process of continuous improvement. I’ve given her space and support to aim higher to foster improvement and growth.

Purpose | Understand WHY you do what you you do. I can’t stress this enough. It’s a known fact that humans are intrinsically motivated by the idea of fulfilling a purpose. Purpose is what gets you out of bed in the morning. Those who believe they are working toward something larger than themselves are often the most hard-working, productive and engaged. Find purpose in your work. Connect it to a larger cause. Volunteer, give back, meditate on compassion, help others. During a crisis, the people who cope the best are those who help others. When we’re motivated by a spirit of generosity or altruism, we benefit as much as those on the receiving end. It’s called the Helper’s High and research shows that it decreases cortisol in the body and predicts better long-term health. With all the excess stress hormones flowing through our body these days, it’s more important now more than ever to be proactive with your health.

-

Pelvic Proprioception: It’s All In The Hips!

You often hear how important it is to activate the glutes during running, but have you ever tried, simply speaking? It's not as easy as it sounds. But what if you just spend a bunch of hours in the gym doing leg presses, squats and deadlifts to make the hips stronger? Unfortunately, that doesn't translate to running as seamlessly as you think. Research shows that, without neuromuscular retraining, strengthening these muscle groups will not lead to a change in movement patterns.1 You can spend a bunch of time isolating certain muscle groups but that won't help you run any better. You need to train movement patterns, not muscles.

Jay Dicharry, a physical therapist and author of Running Rewired makes one of my favorite analogies: "You can't make toast if your toaster isn't plugged in". Heavy squats and deadlifts won't fix the problem. It’s just like cramming more bread into the toaster that isn't plugged in. Change requires teaching the brain and body to reprogram movement patterns.

Running gait is reflexive and habitual. Altering any motor pattern that has become habituated over many years can be difficult, especially considering a runner who runs 20 miles a week. At 1000 steps per mile, this individual can log over 1 million foot strikes per year. But the beautiful thing about the brain is its plasticity. You can modify your form, but you must work on coordinating extra input from the brain into your normal movement patterns. At first, it requires complete, conscious focus on the task. Over time, the new movement pattern can become fully rewired into the brain and reflexive. Altering a motor pattern like this takes both guidance, practice and patience to alter.1

Pelvic Proprioception

So this brings us to our topic of the hips and pelvic proprioception. Proprioception is our sense of the body's position and orientation in space. We use this feedback to move all the time. Activating the glutes during running gait initially requires one to be able to sense how the pelvis is moving in space. I think of the hips as both the steering wheel of the lower body and the fulcrum upon which our core is balanced. Pelvic proprioception requires both glute and core input, adequate mobility and stability.

During running gait, the glutes are supposed to effectively fire concentrically as you extend your hip and push off the ground behind you. In an ideal world, it is reflexive and subconscious (you don’t think about it). But for most of us in our sedentary culture, we require extra input. However, it's not as easy as just 'thinking' about squeezing your glutes. And doing a bunch of single legs squats in the gym will not magically plug them in when you run.

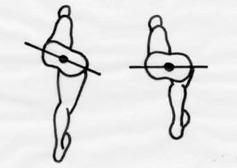

A runner's ability to effectively activate the posterior hip depends not only on adequate neurons going to the muscle, but also the position of the pelvis. The ability to properly extend the hip at this late stance phase of gait will determine how inhibited or accessible the glutes are. The pelvis moves in three planes of motion when we walk and run. A lot of focus these days involves minimizing pelvic movement in the frontal plane, what we think of as hip drop or pelvic drop (gluteus medius strengthening, anyone?). But we forget that pelvic rotation in the transverse plane is equally as important. A study involving robotic gait assistive devices reduced these pelvis rotations and found that stride length, step length, and gait velocity were significantly reduced while stance phase was increased2. Pelvic rotation is critical for healthy gait and improved performance.

Pelvic rotation in the transverse plane – as your knee drives out in front of you, your ipsilateral hip should follow

Pelvic rotation in the transverse plane – as your knee drives out in front of you, your ipsilateral hip should followSo how does this work?

Proper pelvic rotation requires adequate hip extension and hip internal rotation in this extended position. Think of the body as a dreidel spinning in place. That is essentially how your pelvis should rotate around your spine when you run and walk, back and forth around a vertical axis. If your pelvis doesn't move the way it's supposed to either due to mobility restrictions or motor control issues, your body is going to look for that movement elsewhere (i.e. the hip joints themselves, the lumbar spine, excessive arm swing, etc), which can create overuse injuries over time. A lack of mobility and motor control at the hip and pelvis will also inhibit a runner’s ability to extend the hip properly, thus diminishing the chances of firing the glutes effectively.

Why is pelvic rotation important? By thinking about the hips moving forward with the knee and the body, you reduce any excessive vertical oscillation (up and down bouncing that takes away from the forward momentum of the body)3. Not only does it allow you to effectively use the glutes during push-off, but by rotating your hip around the vertical axis each time you drive your knee forward, you can actually gain 1-4 inches with each stride. Decreasing risk of injury and improving performance? Now that's a win-win.

Where do I start?

The first step? Work on retraining that motor pattern. Below is a three-step running-specific progression to work on controlling your pelvis about that transverse plane. The movements are subtle. I’m not asking you to swing your hips around uncontrollably! Start with the first exercise and when it becomes automatic and reflexive, progress to the next. When you first start these exercises, they may require a lot of cognitive focus on the task at hand. But after adequate repetition and consistency, this should become intuitive. For further guidance and education on gait mechanics and injury prevention, schedule an appointment with us today!

Single Leg Pelvic Rotation with Knee Drive

Start off leaning into the wall, as you drive one knee forward, rotate the pelvis to drive that same side hip bone further forward with the knee. The key is to keep that knee moving straight forward (don't let it cross over the center of the body). This slight rotation of the pelvis creates relative internal rotation and extension of the stance leg, consequently turning on the glutes. Remember to keep the core engaged as well throughout.

Single Leg Pelvic Rotation with Triple Extension

Start off leaning into the wall, as you drive one knee forward, rotate the pelvis to drive that same side hip bone further forward with the knee. The key is to keep that knee moving straight forward (don't let it cross over the center of the body). This slight rotation of the pelvis creates relative internal rotation and extension of the stance leg, consequently turning on the glutes. Remember to keep the core engaged as well throughout.

Single Leg Step-Up with Resisted Pelvic Rotation

The more advanced progression requires single leg stability and balance and core control. With a resistance band around your hips tied behind you, step up onto a box. As you drive your knee forward, your same hip bone should also point and move forward against the resistance of the band. Keep your core engaged!

References:

- Davis IS, Futrell E. Gait Retraining: Altering the Fingerprint of Gait. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2016;27(1):339-355. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2015.09.002

- Mun KR, Guo Z, Yu H. Restriction of pelvic lateral and rotational motions alters lower limb kinematics and muscle activation pattern during over-ground walking. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2016;54(11):1621-1629. doi:10.1007/s11517-016-1450-8

- Saunders JB, Inman VT, Eberhart HD. The major determinants in normal and pathological gait. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1953;35-A(3):543-558.

-

Don’t Skip the Warm-Up and Cool-Down

You’ve probably been told not to, and yet you’ve probably done it countless times... skipped your warm-up or cool-down (citing lack of time as the primary reason). The warm-up and cool down are actually important parts of a workout routine. Not only do they help you get the most out of your session, but they also reduce risk of injury. When you’re already investing so much time and energy into your sport, why would you NOT want take advantage of your full performance capabilities?

Warm-ups generally involve doing your sport but at a reduced intensity level, helping your body prepare for the activity. Physiologically speaking, it revs up your cardiovascular system by dilating blood vessels and increasing core temperature, heart rate and blood flow to muscles. At the initial onset of exercise, your heart rate abruptly increases due to a complex series of reactions from your nervous system. It requires at least a few minutes to normalize back to a steady state rate.

Cool-downs are equally as important. An abrupt stop can cause lightheadedness, as your blood pressure and heart rate can drop rapidly. A proper warm-up and cool-down may add a few extra minutes to your workout, but it decreases the stress on your heart and muscles and can greatly reduce risk of injury and adverse reaction during exercise.

There are various ways to warm-up and cool-down for each sport, but the principles are essentially the same. Especially for a sport that can involve more than one training session a day, it’s important to get that warm-up and cool-down in between.

For a generally easy session, it’s recommended to spend a good 5-10 minutes warming into the activity. For higher intensity workouts, 10-15 minutes. A cool-down of 5-10 minutes is also adequate enough to let the heart rate come down while allowing blood flow to continue through the muscles. We’re sharing a few tips for a proper warm-up for both cycling and running, to help you get the most out of your sessions.

CYCLING

On the bike, warm-up for 10-15 minutes at 40-60% of your threshold power or effort. Feel free to throw in some short high cadence spin-ups to get the legs and heart going before any intensity in the main set. This is also a good time to incorporate drills (i.e. cadence work, single leg drills) to improve pedaling efficiency.RUNNING

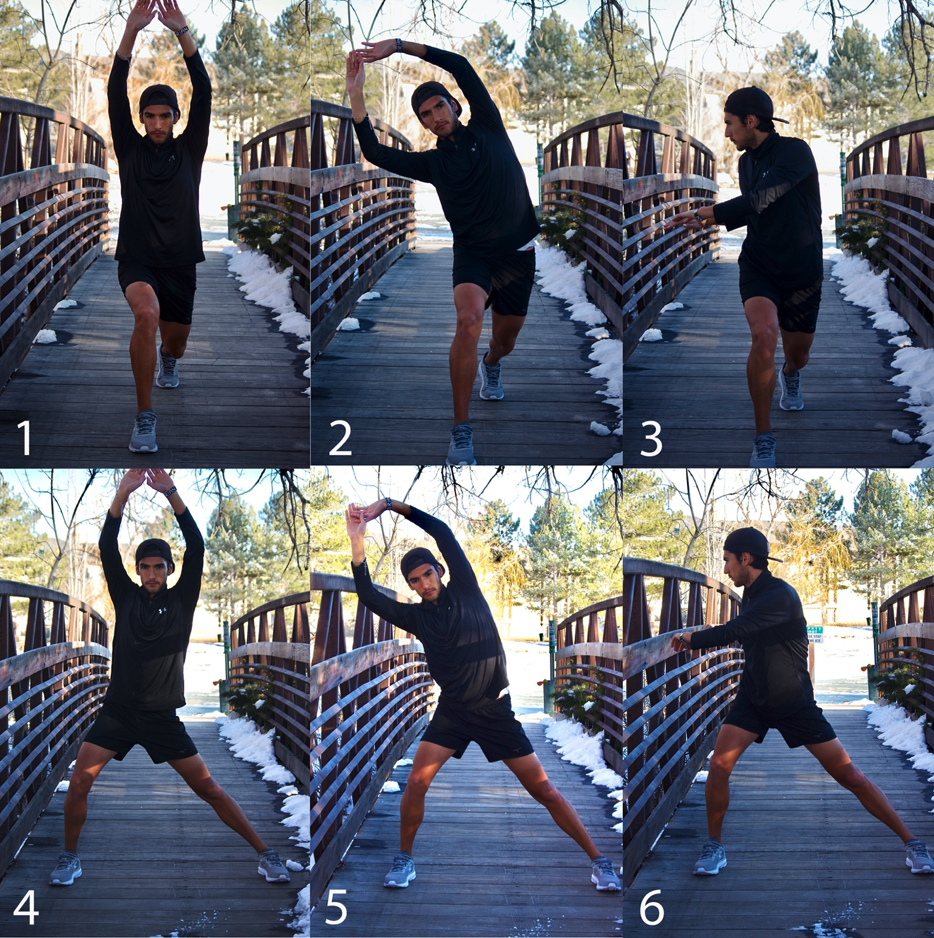

Because running is a weight-bearing sport, it puts a lot more stress on the body than cycling. A proper run warm-up will typically consist of mobility and muscle activation activities (see below) and 10-15 minutes of easy, aerobic running. For a speed or high intensity workout, include more dynamic form drills such as high knees, butt kicks, various types of skips and side shuffles.So, what’s the deal with all this talk of mobility and muscle activation? Well, if you’re like most of us, you probably spend a good chunk of your day sitting. That can equate to short muscles on the front of the hip (hip flexors) and inhibited muscles on the backside (glutes). Our glutes are huge power generators while running and are important for stability up and down the kinetic chain. When we sit, not only are they inactive, but they also have decreased blood flow to the tissues. For some, these muscles need extra attention to wake-up before going out for that run. Below are three great exercises to improve hip mobility and glute activation pre-run.

Lunge Matrix Stretch

This is a good, dynamic stretch to open up the hip in all planes of motion. Start off with a lunge to the front. With your arms, reach down then up, side bend right and left, and then rotate to the right and left. Repeat the same arm movements while lunging out to the side.

Side Steps with Band

Keeping knees slightly bent, toes pointed forward and feet parallel, step out to the side and follow with the other foot, keeping tension in the band at all times. You’ll want to feel the muscles on the outside/back of the hip working. For one level easier, place the band just above the knees and keep those knees in line with your toes. For one step harder, place the band around your toes and work on keeping your knees in line and feet parallel.

Standing Fire Hydrants

This is a great two-for-one exercise, targeting glutes on the standing leg, and glutes on the moving leg. With a resistance band just above the knees, stand on one leg and bend the opposite knee. Open up that knee out to the back corner, mimicking what a dog does when he needs to go to the, well, you know. Be sure you have a soft bend in your standing leg and that your knee isn’t locked out.